ANAL CONDITIONS

Colorectal Surgeons Sydney are experienced with a variety of Anal Conditions, including:

ANAL ABSCESS

An anal abscess results when a perianal gland becomes infected. It causes severe pain in the region around the anus. There may also be discharge of pus or blood from the anus with an offensive odour.

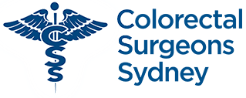

TYPES

Perianal abscesses can be small and localised to the anal region (perianal abscess), be confined to the space between the internal and external anal sphincter (intersphincteric abscess), be large extending into the buttock region (ischiorectal), or rarely be high above the muscular floor of the pelvis (supralevator abscess).

CAUSE

Most abscesses result from infection of one of 15-20 perianal glands located in the anal canal (Cryptoglandular hypothesis). This is more common in young adults, but can occur at any age. The reason why some people develop it, and others don’t is not known. A less common cause of perianal abscess common in smokers is Hidradenitits suppurativa, Crohn’s Disease is occasionally the cause of a perianal abscess resulting from an anal fistula.

SYMPTOMS

Pain, swelling, redness and discharge of mal-odorous pus from the perianal region are classical signs.

Investigation

The diagnosis is made clinically, and confirmed by an Examination Under Anaesthesia (EUA), where the abscess is also drained.

Course

Over half of perianal abscesses will never recur once incised and drained. Some develop an anal fistula which is a communication between the internal anus and the external skin. If an anal fistula develops it may require further surgery or the insertion of a silastic seton. This is like a rubber band that allows the abscess drainage site to remain open to allow it to drain properly until the inflammation and infection has resolved.

Surgical management

Incision and drainage (lancing) under anaesthesia is the treatment for an acute perianal abscess. Antibiotics for a period of time may also be needed.

What to expect pre and post operatively following anal abscess surgery

Incision and drainage (lancing) under anaesthesia is the treatment for an acute perianal abscess. Antibiotics for a period of time may also be needed.

-

Fasting and Bowel Preparation

Unless you are also having a colonoscopy, a normal diet without a bowel prep, is required the day before surgery. You need to fast from midnight the night before if your surgery is scheduled for the morning, or from 7am if scheduled for the afternoon. You will be admitted as a day-stay procedure. You will receive a Fleet® enema 1 hour prior to your operation.

-

Recovery and transport

Following your procedure, you will recover for an hour until the effects of sedatives have worn off. You should not drive yourself home after your procedure and should have someone organised (a friend or relative) to accompany you.

-

Bleeding

Spotting of blood or persistent minor oozing will occur for 5 days following your procedure, and a sanitary napkin changed once to twice daily will be needed to prevent staining of your underwear. Bleeding will typically occur after opening your bowels. If the bleeding is more than a couple of teaspoons a day, notify your surgeon.

-

Laxatives

You should remain on regular laxatives and simple analgesics for 1 week. A tablespoon of natural psyllium husk (Metamucil® or Fibogel®) twice daily, and 30ml of lactulose (Duphalac®) once to twice daily is recommended.

-

Pain control

For pain, a non-steroidal is recommended such as 400mg of ibuprofen (Brufen®) along with 2 tablets of paracetamol. This should be taken regularly three times a day for five days. Opioid medications (Endone) may sometimes be needed, but should be used sparingly as they cause constipation.

-

Antibiotics

After discharge from hospital you may require antibiotics to treat ongoing infection. Oral cephazolon (Keflex®) and Metronidazole (Flagyl®) may be needed for 5 days (provided no allergies exist).

-

Dressings

Occasionally you may be sent home for daily dressings for up to a week, which is often performed by a community nurse or your local general practitioner. If an anal fistula was found at the time of the incision and drainage procedure, then you will be sent home with a silastic seton in place. This is about the size and consistency of a rubber band and is passed through the tract of the fistula to allow ongoing drainage of the abscess.

-

Sitz baths

Twice daily warm to hot salt water (Sitz) bathing to the anal region is soothing and antiseptic, and should be done for 1 week following your procedure. Put a handful of salt into a shallow bath of warm-to-hot water and sit there for 10-15 minutes.

-

Follow-up

You should follow up with your colorectal surgeon in 6-8 weeks following your surgery to review your wound and discuss further management if indicated.

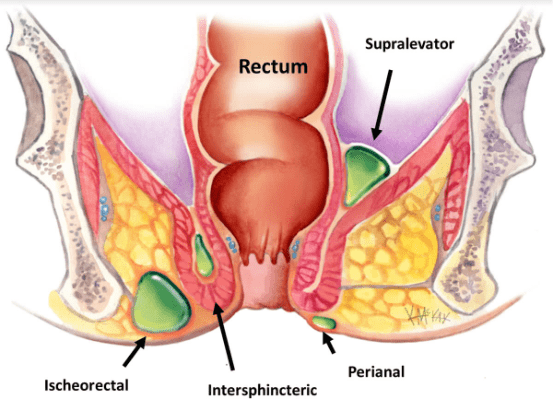

ANAL CANCER

Anal cancer (also called Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Anus or SCCA) is a skin cancer that arises from inside the anal canal or from the skin around the anus (anal verge).

CAUSE

Risk factors for anal cancer include immunodeficiency (e.g. HIV, transplant patients), those who have had previous Anal Warts due to the Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) serotypes 16 & 18, and those with Anal Intraepithelial Neoplasia (AIN). The estimated life time risk of anal cancer in HIV-negative men who have sex with men (MSM) is 30 times that of the average population. The lifetime risk of anal cancer in HIV-positive men who have sex with men (HIV-MSM) is 100 times that of the average population.

SYMPTOMS

Anal cancer may be felt as a lump on digital rectal examination (DRE), or may not be noticeable at all. It may bleed from time to time.

PREVENTION

Since February 2013, the HPV vaccine (Gardasil®) has been provided free of cost through the school-based program for males and females aged 12-13 years occurring in the first year of secondary school.

This vaccine has been shown to reduce the risk of anal and cervical cancer by targeting the Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) serotypes 16, 18, 6 and 11. There is possibly a very small advantage to those already with HPV infection also having the vaccine to help them eliminate the wart virus however this is contentious and remains debated.

Course

Over half of perianal abscesses will never recur once incised and drained. Some develop an anal fistula which is a communication between the internal anus and the external skin. If an anal fistula develops it may require further surgery or the insertion of a silastic seton. This is like a rubber band that allows the abscess drainage site to remain open to allow it to drain properly until the inflammation and infection has resolved.

SCREENING

Screening of high risk populations such as HIV men who have sex with men (HIV-MSM) and those with anal warts due to HPV infection is recommended, however there is much debate about the best method for screening. Screening methods most commonly used include the Pap Smear and anoscopy after painting the area with vinegar (acetic acid). These tests will allow for identification of those with anal dysplasia (AIN) which is a known risk factor for anal cancer. High risk populations (e.g. HIV-msm) and those with high grade AIN should have annual digital rectal examination (DRE).

PAP SMEAR

The PAP smear used for women to detect early cervical cancer, can also be used in high risk groups (e.g. those with HIV or HPV infection) to detect early anal cancer however its accuracy(sensitivity) is only 70%, therefore this practice is not endorsed by current guidelines.

ANOSCOPY

Anoscopy involves viewing the anal region under magnification after the application of acetic acid (vinegar) to reveal areas of abnormality. It is currently not widely used as a screening tool, due to issues related to accuracy of this test and issues related to patient discomfort [3]. Its main role is in screening the high risk population (e.g. HIV and HPV infected), where high resolution anoscopy is likely to be superior to conventional anoscopy [2]. High resolution anoscopy is not widely available with only 5 centres throughout Australia having this technology. Therefore high resolution anoscopy is mainly used for research purposes.

DIGITAL RECTAL EXAMINATION

Annual digital rectal examination (DRE) in the high risk HIV-MSM group is likely to be the most effective screening method for picking up early anal cancer, and is currently the only screening method recommended.

INVESTIGATION

Any suspicious lesion or lump in the anal region should be examined and biopsied. Four quadrant biopsies inside and outside of the perianal region are required in the high risk HIV-MSM patients where AIN status needs to be determined. Low grade anal neoplasia (AIN1) is not precancerous and does not progress to high grade neoplasia (AIN3), but low grade neoplasia (AIN1) is still considered a risk factor of anal cancer. High grade neoplasia (AIN3) is a pre-cancerous condition with risk of progression over time to invasive carcinoma. Once AIN has been confirmed on biopsy, there is currently no benefit in doing regular further biopsies. Rather, digital rectal examination should be performed annually to pick up early cancer.

COURSE AND PROGNOSIS

Anal cancer is locally aggressive, but distant spread (metastases) less common than many other cancers. It responds well to chemoradiotherapy. Overall survival is 69% at 5 years, but is dependent on the stage at which it is picked up.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Very small anal cancers can be managed with surgical excision alone provided this surgery does not involve damage to the anal sphincter. Superficially Invasive Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Anus (SISCCA), refers to anal cancers less then 3mm deep and less than 7mm wide with good evidence that wide local excision with preservation of the anal sphincter gives excellent curative rates without the need for further radiotherapy. However, for lesions larger than this, the management is primary chemoradiotherapy and not surgery.

However, your colorectal surgeon is important in making the diagnosis and the ongoing surveillance of anal cancer following chemoradiotherapy treatment. Occasionally biopsies are required after radiotherapy treatment to confirm that treatment has been successful. This should not occur before 12 weeks have passed since finishing therapy. Occasionally salvage surgery is required after failed response to radiotherapy. This can range from local excision with skin grafting to more radical surgery including removal of the anus and rectum (abdominoperineal resection) with the creation of a permanent stoma.

CHEMORADIOTHERAPY

Anal cancer responds well to radiotherapy combined with a small dose of chemotherapy (mitomycin C or cisplatin), with surgery as primary treatment only used for Superficially Invasive Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Anus (SISCCA), or for larger cancers where primary chemoradiotherapy has failed.

WHAT TO EXPECT PRE AND POST OPERATIVELY FOR PERIANAL BIOPSY OF POSSIBLE ANAL CANCER

-

Fasting and Bowel Preparation

Unless you are also having a colonoscopy, a normal diet without a bowel prep, is required the day before surgery. You need to fast from midnight the night before if your surgery is scheduled for the morning, or from 7am if scheduled for the afternoon. You will be admitted as a day-stay procedure.

-

Recovery and transport

Following your procedure, you will recover for a hour until the effects of sedatives have worn off. You should not drive yourself home after your procedure and should have someone organised (a friend or relative) to accompany you.

-

Bleeding

Spotting of blood will occur from the biopsy sites. A sanitary napkin will be needed to prevent staining of your underwear.

-

Pain

For pain, a nonsteroidal is recommended such as 400mg of ibuprofen (Brufen®) along with 2 tablets of paracetamol. This should only be taken if needed and can be taken up to three times a day for five days. Opioid medications (Endone®) can usually be avoided. If required, they should be used sparingly as they cause constipation.

-

Cleanliness

Excessive cleaning or scratching with abrasive toilet paper should be avoided. Washing with water or using baby wipes is preferable.

-

Follow-up

You should follow up with your colorectal surgeon in 6-8 weeks following your surgery to review your condition and discuss further management if indicated.

REFERENCE LIST

- Palefsky JM, Holly EA, Hogeboom CJ, et al. Anal cytology as a screening tool for anal squamous intraepithelial lesions. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 1997;14:415‐422

- Weis SE. Vecino I. Pogoda JM. Susa JS. Nevoit J. Radaford D. McNeely P. Colquitt CA. Adams E Prevalence of anal intraepithelial neoplasia defined by anal cytology screening and high-resolution anoscopy in a primary care population of HIV-infected men and women. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 54(4):433-41, 2011 Apr.

- Fox P. Anal cancer screening in men who have sex with men. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2009 Jan;4(1):64-7. Review.

ANAL FISSURES

An anal fissure is a tear or split in the lining of the anus (anal mucosa). This if often due to constipation with firm stools tearing the mucosa on defecation. Anal fissures result in severe pain on defecation, with anal sphincter spasm, and further tearing. This often leads to the avoidance of defecation, establishing a vicious cycle of constipation and repeated anal fissuring.

SYMPTOMS

Symptoms include pain and bleeding from the anus when passing a bowel motion.

CAUSE

Common causes in adults include constipation and trauma to the anus. Rarely it is due to Crohn’s Disease of the anus. Around half of cases heal by themselves with proper self-care and avoidance of constipation. However, healing can be a problem if the pressure of passing bowel motions constantly reopens the fissure. Treatment options include the use of bulking agents such as Metamucil ® or Fibogel® to loosen the stool and laxatives such as lactulose (Duphulac®) or osmotic laxatives such as Movicol®. The topical application of medications to relax the sphincter such as Rectogesic® or diltiazem may help. These can also be combined with botulin toxin (Botox®) injections to the internal sphincter to allow temporary relaxation of the anus to allow for healing of the fissure. If these measures failure, surgery may be indicated, where a small proportion of the internal sphincter is cut.

COMPLICATIONS

Acute anal fissures are usually a benign condition not associated with more serious diseases, such as bowel cancer. Failure to heal can result in the development of a chronic anal fissure. Over time, this can cause extensive scar tissue at the site of the fissure (sentinel pile). Rarely, anal fissures can form an anal fistula (an abnormal tract that joins the internal anus to the external skin surrounding the anus).

DIAGNOSIS

An anal fissure is largely a clinical diagnosis based on the typical history including pain and bleeding on defecation, along with the classic features of pain on examination, and a visible fissure in the midline of the anus. Commonly, examination is poorly tolerated and proper diagnosis requires examination under anaesthetic.

TREATMENT

-

Lifestyle Modification

Simple lifestyle modifications to prevent constipation include drinking plenty of water (six to eight glasses of water a day), having a diet high in fibre, and exercising regularly. To allow the fissure to heal we suggest showering or bathing, or using baby wipes after every bowel motion and taking regular warm-to-hot salt water (Sitz) baths, which involves sitting in a shallow bath of water for around 20 minutes. This is soothing as well as cleansing.

-

Medical Management

Once a fissure is established, the above measures rarely result in healing, and medical treatment is often required. Stool softeners containing non-soluble fibre including natural psyllium husk (Metamucil®) or ispaghula husk (Fibogel®) are recommended. Laxatives are commonly required and include lactulose (Duphalac®) sterculia (Normacol®) or osmotic agents containing magroglol polymers and sodium phosphate (Movicol®). Pain relief may be required and include over the counter non-opioid based analgesics including non-steroidal medications such as ibuprofen (Brufen®) and simple paracetamol (Panadol®). Opioid medications containing morphine-like agents should be avoided as they cause constipation, which exacerbates the condition.

-

Topical gels

Topical nitrates such as 0.2% glycerine trinitrate (Rectogesic®) and 1% isosorbide dinitrate (Isordil®) work by relaxing the internal sphincter, and preventing spasm. Headaches are a side effect of Rectogesic® and are less common with Isordil®. In breast-feeding mothers, nitrates should not be used, and calcium channel blockers (diltiazem) in 2% gel form is an effective alternative. These ointments are all applied to the anal sphincter three times a day, and must be used for 6 weeks for success. These agents are effective in over half of cases.

-

Neurotoxin Injections

Neurotoxin (Botulin toxin A) injections work by temporarily paralysing a portion of the internal sphincter muscle. Botox has the advantage of being effective in 60-80% of cases as well as being reversible and repeatable. Unfortunately, it is not covered by private health insurance or medicare in most hospitals, and costs $500 per injection. There have been reports of temporary incontinence in 20% of patients. Combination Botulin toxin A injections and topical gels such as those already mentioned are more likely to work than either on its own.

-

Surgery

Surgery is indicated for the anal fissure that fails to heal despite those non-operative measures described above. The chronic anal fissure present for more than 6 weeks, or the painless fissure that is not in the midline may require a biopsy to exclude Crohn’s disease or squamous cell carcinoma.

-

Lateral sphincterotomy

Relaxation of the anal sphincter may be achieved by performing a lateral sphincterotomy. In this procedure less than a third of the inner anal sphincter is divided at the level of the anal fissure, to provide relief from anal sphincter spasm to allow healing of the fissure. This procedure is called a lateral sphincterotomy and is extremely effective with a success of over 90%. The long-term side effects include incontinence in up to 3% of cases.

-

Anoderm or rectal advancement flaps

Anal fissures that fail to heal with the above measures, may need to be surgically removed, and repaired using a flap. This procedure is particularly suited for the chronic painless fissure, where anal pressures are normal suggesting that anal spasm is not the cause. In this procedure, the fissure and associated scar tissue is removed, and the lining (mucosa) of the anus or rectum along with the underlying muscle is mobilised as a flap to cover the defect.

-

Lateral sphincterotomy

WHAT TO EXPECT PRE AND POST OPERATIVELY FOR ANAL FISSURE SURGERY

-

Fasting and Bowel Preparation

Unless you are also having a colonoscopy, a normal diet without a bowel prep, is required the day before surgery. You need to fast from midnight the night before if your surgery is scheduled for the morning, or from 7am if scheduled for the afternoon. You will be admitted as a day-stay procedure. You will receive a fleet® enema 1 hour prior to your operation.

-

Recovery and transport

Following your procedure, you will recover for an hour until the effects of sedatives have worn off. You should not drive yourself home after your procedure and should have someone organised (a friend or relative) to accompany you.

-

Bleeding

Spotting of blood will occur for 5 days following your procedure, and a sanitary napkin will be needed to prevent staining of your underwear. Bleeding will typically occur after opening your bowels. If the bleeding is more than a couple of teaspoons a day, notify your surgeon.

-

Laxatives

You should remain on regular laxatives and simple analgesics for 1 week. A tablespoon of natural psyllium husk (Metamucil® or Fibogel®) twice daily, and 30ml of lactulose (Duphalac®) twice daily is recommended.

-

Pain control

For pain, continue regular topical application of glycerine trinitrate Rectogesic®) three times daily for up to six weeks following your surgery is recommended. Simple oral analgesics may occasionally be needed, and a non-steroidal is recommended such as 400mg of ibuprofen (Brufen®) along with 2 tablets of paracetamol. This should be only if required, and can be taken up to three times a day for five days. Opioid medications (Endone) are rarely indicated and should be avoided as they cause constipation.

-

Sitz Baths

Twice daily warm to hot salt-water (Sitz) bathing to the anal region is soothing and antiseptic, and should be done for 1 week following your procedure. Put a handful of salt into a shallow bath of warm-to-hot water and sit there for 10-15 minutes.

-

Follow-up

You should follow up with your colorectal surgeon in 6-8 weeks following your surgery to review your wound and discuss further management if indicated.

REFERENCES

- Perry WB. Dykes SL. Buie WD. Rafferty JF. Standards Practice Task Force of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Practice parameters for the management of anal fissures (3rd revision). Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 53(8):1110-5, 2010 Aug.

ANAL FISTULA

An anal fistula is a communicating tract between the inner anus or rectum and the external skin surrounding the anus. It begins as a superficial ulcer (Figure 1), that becomes infected creating an anal abscess that subsequently bursts leaving a communicating tract between the internal anus and the external skin of the perianal region. It causes a chronic discharge of pus that typically has an offensive odour.

TYPES

A perianal fistula can be short and superficial, not involving the anal sphincter (submucosal fistula) or can be long and deep, involving the just the internal anal sphincter (intersphincteric fistula) or both anal sphincters (transphincteric fistula or extrasphincteric). Most fistulae are low arising from low within the anal canal. Rarely fistulas are high, arising from above the anal canal (supralevator fistula).

SIMPLE FISTULAE

Simple fistulae are those with a single tract that involves less than 30-50% of the external anal sphincter. The preferred treatment of a simple fistula is to lay it open [1]. This is a small operation under general anaesthetic, in which a probe is placed in the fistula, and the overlying skin cut to allow the tract to heal as a shallow ulcer.

COMPLEX FISTULAE

Complex fistulae, are those with multiple tracts, those that involve more than 30-50% of the external sphincter, those that involve the anterior half of the anus (in women), any fistula as a result of radiation or Crohn’s disease, and those arising in someone with already compromised sphincter function (i.e. weak anal tone prone to incontinence). These cannot simply be laid open, and often the first step is to control the sepsis by inserting a seton (figure 2).

CAUSE

Anal fistulae result when an anal abscess bursts into the tissues surrounding the anus. This condition is common in young adults, but can occur at any age. The reason why some people develop a fistula, and others don’t is not known. Smoking and Crohn’s disease have both been shown to increase your risk of developing a fistula. The success of surgery for the treatment of fistulae due to Crohn’s disease or in the smoker is considerably lower than for other fistulas. Infliximab infusions have been shown to increase the success of fistula closure in Crohn’s disease.

SYMPTOMS

A chronic discharge of malodourous pus from the perianal region is the usual feature of an anal fistula. This is often followed a period of intense perianal pain that coincides with the time of abscess formation.

INVESTIGATION

The diagnosis is made clinically, and confirmed by an Examination Under Anaesthesia (EUA), where a probe is gently inserted into the fistula tract to confirm a communication between the outside perianal skin and the internal lining of the anal canal. Occasionally Endo Anal Ultrasound (EAU) or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) are needed to determine the number and direction of fistula tracts, and to determine the amount of muscle sphincter involved prior to any planned surgery.

COURSE

The initial management of a fistula is to drain it. This is a small surgical procedure performed under general anaesthetic where a silastic seton (similar in size and consistency to a rubber band) is passed through the fistula tract and tied in place. This allows any pus to drain, and inflammation to settle. A course of antibiotics may also be required.

SIMPLE FISTULAE

Within 6 weeks, the condition should be much improved, and you will need to be re-examined by a colorectal surgeon to determine if the internal opening of the fistula is low (and safe to lay open) or not. This is a simply procedure where a Lockhart Mummery probe is passed through the fistula tract and using diathermy, the roof of the tract incised turning the fistula tract into an ulcer. This will slowly heal over 6-12 weeks.

If the internal opening of the fistula tract is high, it involves too much of the internal sphincter, and it is not safe to incise, as loss of this vital muscle will result in incontinence. Therefore, at this point there are 4 options:

- Remove the seton;

- Tighten the seton (repeated every 6-12 weeks);

- Remove the seton and use glue or a plug to seal the tract;

- Leave the seton in place for 6 months to allow “maturing” of the fistula tract prior to planned surgical repair.

-

Remove the seton

If the seton has been in for only 6 weeks, and the infection has settled, simply removing the seton has been shown to be effective in up to 75-80% of cases [3,4]. The success following simple removal of the seton is reduced to less than 50-60% for patients with Crohn’s disease.

-

Tighten the seton

Sequential tightening of the seton under anaesthetic every 6-12 weeks leads to the seton eventually cutting through the muscle sphincter. Because the cutting process is very slow, it allows scar tissue to form between the cut ends of the sphincter muscle, allowing the circular sphincter muscle to still function as a sphincter. This whole process can take anywhere from 3-12 months to complete.

-

Remove the seton and use glue or a plug to seal the tract

A vast number of plugs and glues have been used to try to seal fistula tracts. The argued benefit of these techniques is that they preserve the anal sphincters. Several products are commercially available and treatment involves single or repeated injection into the external opening. Initial studies were promising with healing rates of up to 70% with no studies reporting impairment of continence. However more recent studies looking at long-term healing rates show disappointing recurrence rates as high as 75%. [8-10]. Therefore, a selective approach is recommended, with only some fistulae suitable for plugs. There is some evidence suggesting that long tracts greater than 4cm in length are more likely than short tracts to heal with these techniques.

-

Leave the seton in place for 6 months to allow “maturing” of the fistula tract prior to planned surgical excision and repair.

If the fistula tract is high, it is unsafe to cut the anal sphincter, and the seton is left in place for 6 months to allow the fistula tract to “mature”, with epithelialization of the tract occurring. Once this maturation process has occurred, a surgical repair can then be performed. This may involve simple ligation and excision of a portion of the fistula tract, without the use of a flap (i.e. LIFT procedure) or may involve excision of the entire length of fistula tract followed by a formal flap repair to cover the internal opening.

If the internal opening is very high in the anal canal a rectal advancement flap is performed using a flap of mucosa and the underlying muscle to cover the internal opening. If the internal opening is low enough in the anal canal, an anoderm V-Y advancement flap may be preferable. Both these flap repairs also involve repairing the sphincter, and usually result in the external opening remaining open to allow for drainage.

WHAT TO EXPECT PRE AND POST OPERATIVELY FOLLOWING ANAL FISTULA SURGERY

-

Fasting and Bowel Preparation

Unless you are also having a colonoscopy, a normal diet without bowel preparation, is required the day before surgery. You need to fast from midnight the night before if your surgery is scheduled for the morning, or from 7am if scheduled for the afternoon. You will be admitted as a day-stay procedure. You will receive a fleet® enema 90 and 60 minutes prior to your operation.

-

Recovery and transport

Following your procedure, you will recover for an hour until the effects of sedatives have worn off. You should not drive yourself home after your procedure and should have someone organised to accompany you home.

-

Bleeding

Spotting of blood or persistent minor oozing will occur for 5 days and a sanitary napkin changed once to twice daily will be needed to prevent staining. Bleeding will typically occur after opening your bowels. If the bleeding is more than a couple of teaspoons a day, notify your surgeon.

-

Laxatives

A tablespoon of natural psyllium husk (Metamucil® or Fibogel®) three times daily is recommended the first 2 weeks after surgery

-

Pain control

A non-steroidal is recommended such as 400mg of ibuprofen (Brufen®) along with 2 tablets of paracetamol up to three times a day. Opioid medications (Endone) may sometimes be needed, but should be used sparingly as they cause constipation.

-

Antibiotics

You may require antibiotics to treat ongoing infection. Oral Augmentin Duo Forte® twice daily (if not allergic to penicillin) for 5 days is adequate. Otherwise cephazolon (Keflex®) &metronidazole (Flagyl®).

-

Dressings

A simple pad is all that is usually required, changed twice daily.

-

Sitz baths

Twice daily warm to hot salt water (Sitz) bathing to the anal region is soothing and antiseptic, and should be done for 1 -2 weeks following your procedure. Put a handful of salt into a shallow bath of warm-to-hot water and sit there for 10-30 minutes.

-

Follow-up

You should follow up with your colorectal surgeon in 6 weeks following your surgery to review your wound and discuss further management if indicated.

REFERENCES

- Williams JG, Farrands PA, Williams AB, Taylor BA, Lunniss PJ, Sagar PM, Varma JS, George BD. The Treatment of Anal Fistula: ACPGBI Position Statement. Colorectal Disease. 9 (Suppl. 4): 18-50, 2007.

- Sands B, Anderson F, Bernstein C, Chey W, Feagan B, Fedorak R, Kamm M, Korzenik J, Lashner B, Onken J, Rachmilewitz D, Rutgeerts P, Wild G, Wolf D, Marsters P, Travers S, Blank M, van Deventer S. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease. The New England Journal of Medicine New England Journal of Medicine. 350 (9): 876–85, 2004.

- Joy HA, Williams JG. The outcome of surgery for complex anal fistulas. Colorectal Disease. 4: 254-61, 2002.

- Eitan A, Koliada M, Bickel A, et al. The use of the loose seton technique as a definitive treatment for recurrent and persistent high trans-sphincteric anal fistulas: a long-term outcome. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery 2009; 13(6):1116-9.

- Faucheron JL, Saint-Marc O, Guibert L, et al. Long-term seton drainage for high anal fistulas in Crohn’s disease–a sphincter-saving operation? Diseases of the Colon & Rectum 1996; 39(2):208-11.

- Lentner A. Wienert V. Long-term, indwelling setons for low transsphincteric and intersphincteric anal fistulas. Experience with 108 cases. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 39(10):1097-101, 1996 Oct.

- Johnson E, Gaw J, Armstrong D. Efficacy of anal fistula plug vs. fibrin glue in closure of anorectal fistulas. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum 49(3): 371-6, 2006.

- Buchanan G, Bartram C, Phillips R, etal. The efficacy of fibrin sealant in the management of complex anal fistula: a prospective trial. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 46: 1167-74, 2003.9. van Koperen PJ. Bemelman WA. Gerhards MF. Janssen LW. van Tets WF. van Dalsen AD. Slors JF. The anal fistula plug treatment compared with the mucosal advancement flap for cryptoglandular high transsphincteric perianal fistula: a double-blinded multicenter randomized trial. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 54(4):387-93, 2011 Apr.

- Ortiz H, Marzo J, Ciga MA, Oteiza F, Armendariz P, de Miguel M. Randomized clinical trial of anal fistula plug versus endorectal advancement flap for the treatment of high cryptoglandular fistula in ano. Br J Surg. 2009;96:608–612.

- McGee MF. Champagne BJ. Stulberg JJ. Reynolds H. Marderstein E. Delaney CP. Tract length predicts successful closure with anal fistula plug in cryptoglandular fistulas. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 53(8):1116-20, 2010 Aug.

ANAL PAIN

Colorectal Surgeons Sydney are experienced with a range of conditions associated with Anal Pain, including:

COCCYGODYNIA

Coccygodynia refers to pain over the ‘tail-bone” (coccyx). It is more common in women, and can result from trauma such as occurs following a fall or childbirth. It may result from an abnormally large coccyx, or may result from a mobile coccyx. Occasionally it results in chronic arthritis, or bursitis, or the development of a bony spicule that can lead to more chronic pain.

Diagnosis

Examination will typically reveal pain localised to the coccyx, which may even be felt to be mobile, or to have a palpable spur.

Plain x-rays, may reveal bony abnormalities (spicules, tumours, degeneration, metastases). Dynamic x-rays in both the sitting and standing position may reveal a mobile coccyx.

Management

Analgesic, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication may help reduce pain and inflammation.

Hot Sitz baths, heat packs, and donut cushions for sitting, to reduce direct pressure on the coccyx, can often alleviate pain.

Resistant cases

For persistent cases, injection of local anaesthetic with steroids may help.

Surgery

Surgical removal of the ‘tail-bone’ (coccygectomy) is reserved for resistant cases despite the above strategies. Success rates are as high as 90%.

References

- Wray CC, Eason S, Hoskinson J. Coccydnia: Aetiology and treatment. J bone Joint Surg Br 1991; 73:335-338.

HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS

A herpes simplex virus infection of the anal region can produce a pain similar to an anal fissure. Herpes can infect the anal area, either spread by the hands from a cold sore on the face, or transmitted as a sexual infection. At the anus, herpes often forms a crack rather than the small ulcers that tend to occur elsewhere. It can occur in individuals who have never had herpes elsewhere. The soreness occurs in episodes, each lasting for a few days.

A swab to check for the virus as soon as an episode starts can make the diagnosis. Treatment may include topical application of 5% aciclovir (zovirax cold sore cream®) ointment.

LEVATOR ANI SYNDROME

Levator ani syndrome (LAS) is a condition which more often affects women than men, and is thought to result from spasm of the upper most layer of the anal sphincter (puborectalis muscle).

It typically causes a dull aching pain or discomfort of the anus, that lasts more than 20 minutes, and frequently hours to days.

It is often exacerbated by sitting for long periods or lying down, and relieved by walking.

Examination of the anus is usually unremarkable with only palpable tenderness of the levator ani muscles, signifying puborectalis spasm. Anal manometry typically shows increased anal pressures.

Management

The aim of treatment is to reduce anal canal or levator ani tension.

Hot Sitz-baths (38 degrees Celsius) have been shown to be of some use, on their own, as well as in combination with massage and muscle relaxants (diazepam).

Digital massage of the muscle, electrogalvanic stimulation by a rectal probe and biofeedback regimes utilising pressure-measuring probes have variable success [1].

References

- Wald A. Anorectal and Pelvic Pain in Women. J Clin Gastroenterol 2001; 33(4): 283-28

PROCTALGIA FUGAX

Proctalgia fugax (also called Levator Syndrome) is characterised by severe, episodic, anal pain. It can be caused by a spasm or cramping of the anal sphincter muscles (including the pubo-coccygeus or levator ani muscles). It is a diagnosis of exclusion, and provided other conditions that may cause anal pain are excluded, then the approach is generally simple reassurance and symptom control.

Presentation

Proctalgia fugax commonly occurs at night time, causing waking from sleep. It is typically severe and lasts for a few seconds to minutes. It may be associated with back pain, or pain that shoots down the legs.

Who is affected?

The onset can be as early as childhood however it typically presents during young adulthood.

Treatment and prevention

Traditional remedies include warm compress, or warm baths – however the pain is often of such short duration that there is not sufficient time to organise these. In patients who suffer frequent, severe, prolonged attacks, inhaled salbutamol (Ventolin®) has been shown in some studies to reduce their duration. Oral ingestion of calcium channel blockers such as diltiazem (Cardizem®) has also been found to work. Caffeine may relieve pain once ingested. Low dose diazepam at bedtime has been suggested as preventative, but is generally advised against because of its addictive nature.

Surgery is not indicated however there have been reports of the use of botulinum toxin injection in severe cases as a method of relaxing the anal sphincter temporarily.

Pain from the anal region can cause a lot of concern, as it is an unusual experience. The nature of the pain can often be a clue as to the underlying cause however referral to a colorectal surgeon to properly investigate this condition may be indicated.

TYPES OF PAIN

- A knife-like pain when you pass a bowel motion which may last for 10–15 minutes afterwards, is probably caused by an anal fissure. Some people describe it as like ‘passing glass’. In addition to the pain, you may notice some bright red blood on the toilet paper.

- A similar knife-like pain can be caused by herpes simplex virus.

- A nagging, aching discomfort made worse by defecation could be due to haemorrhoids.

- A throbbing pain, worsening over a few days, and bad enough to disturb your sleep, is likely to be caused by an anal abscess.

- Sudden severe spasms of anal pain felt deep in the anal canal lasting seconds to minutes, with no pain between episodes is probably a condition called proctalgia fugax.

- A dull aching pain or discomfort of the anus, that lasts more than 20 minutes, and frequently hours to days, may be due to levator ani syndrome.

- Pain over the ‘tail-bone (coccyx) may be due to coccygodynia.

- A continuous aching pain in the anus in which all of the above causes have been excluded, suggests referred pain caused by a back problem (when a part of the spine presses on a nerve).

ANAL PRURITUS

Anal pruritus (also known as “pruritus ani”) is persistent itching of the skin around the anus. It affects 1- 5% of the population with men more often affected than women. Many present late due to severe embarrassment. It is important not to trivialise the symptoms of this debilitating condition.

This desire to itch can be further exacerbated by increases in moisture, pressure, and rubbing caused by clothing and sitting. Regardless of cause, the problem is exacerbated by a self-escalating “itch-scratch-itch” cycle.

CAUSES

-

Idiopathic

Pruritus ani can be divided into two types: secondary to another condition, and idiopathic, which cannot be attributed to a specific cause [1]. Ideopathic pruritus accounts for more than 50% of patients with this condition.

-

Dermatitis

Skin conditions such as dermatitis, psoriasis and lichen sclerosis have typical plaque appearance and also can irritate the anus and result in anal pruritus. These need to be considered in the differential diagnosis and usually respond to corticosteroid creams. Sometimes punch biopsy is required to get a definitive diagnosis .

-

Foods

Anal itching can be caused by irritating chemicals in the foods consumed, such as those containing spices, hot sauces, and chilli. Excesses in caffeine can also stimulate secretions and bowel function causing loose motions, thereby exacerbating pruritus ani.

-

Moisture

Moisture due to excessive perspiration, frequent liquid stools (diarrhoea), or a degree of faecal incontinence or anal seepage can exacerbate this condition. Moisture can also result from an abnormal passageway communicating between the anus and external skin (anal fistula). A fistula brings contaminated and irritating fluids to the anal area. Moisture can also result from excessive mucous discharge, a common problem with haemorrhoids and rectal prolapse, where the mucous secreting mucosa of the anus and/or rectum drops (prolapses) below the anal sphincter allowing mucous contact with the perianal skin. This mucous is extremely irritant to the skin and causes intense itching. Large external skin tags and external component of haemorrhoids can also interfere with perianal hygiene, exacerbating pruritus ani.

-

Infections

Infection with pinworm is common in those with young children and household pets. Less common is infestation with scabies or mites. These can all be tested for with skin scrapings or the “sellotape test” which are then sent off for viewing under microscopy.

Yeast or fungal infections may occur if there is moisture around the anus and give a characteristic white film appearance overlying the skin. They more often occur in people who are immune-compromised including diabetics, transplant recipients, those taking chemotherapy, and those with HIV. A simple wound swab or scrapings will confirm the presence of hyphi (fungus) on microscopy. Treatment is topical 1% clotrimazole (Canesten®) or 1% terbinafine (Lamisil®) cream.

-

Anal Cancer

Anal cancer is uncommon, as are precancerous lesions (Bowen’s and Paget’s disease). However, when present, they may first present as a perianal itch. It is therefore important for your colorectal surgeon to examine the area, and on occasions a biopsy of any suspicious area may be needed to exclude anal cancer.

-

Treatment

Some colorectal surgeons take a nihilistic approach to the management of pruritus, considering it “incurable”. This is not the case and there is hope even for the most belligerent of cases. Treatment needs to be aimed at identifying & treating reversible causes, and getting severe intractable cases out of the itch-scratch cycle. Correcting maladaptive behaviour with the provision of clear achievable supportive guidelines plays an important role.

-

Cleaning

It is important to clean and dry the anus thoroughly and avoid leaving soap in the anal area. Cleaning efforts should include gentle showering without direct rubbing or irritation of the skin with either the washcloth or towel. A “dabbing” action rather than “rubbing” action should be used for drying. Use of a hair dryer is also an option.

-

Baby wipes or bidet

Baby wipes may be preferable to abrasive toilet paper and can help reduce friction, however perfumed baby wipes should be avoided. Even supposed “flushable” wipes have the potential to block sewer pipes with simple water the best option.

The French bidet used to wash the anal region after a bowel movement is an alternative to baby wipes. The conventional toilet can also have a bidet appliance attached to it. If bidet or wipes are not available or convenient, water or sorbolene cream or water based lubricant placed on toilet paper before wiping will reduce abrasion.

-

Behaviour modification

A small group with pruritus ani may have a degree of obsessive compulsive personality, and this group may require more targeted cognitive behaviour therapy to avoid ritualistic repetitive cleaning practices.

An even smaller group may have acquired their chronic itch through ano-neurotic acts of pleasure. To be fair, everyone with an itch gets immediate pleasure or relief in scratching. It must be emphasised that scratching the affected area is to be resisted, no matter how tempting it may be, as it only aggravates the problem and can lead to bleeding from the anal area and a delay in the recovery process.

-

Underwear

Synthetic underwear should be avoided. Firm supportive cotton underpants are recommended. Initially these may need to be changed more often then once daily if there is significant perianal moisture or exudate. The alternative is to line underwear with an adhesive thin panty liner. A gauze pad or combine, folded in half and placed between the buttocks so that it is in close proximity to the anus, is an effective way of reducing moisture to the region.

-

Underwear

-

Bulking agents

Anal pruritus is often exacerbated by watery stools. A tablespoon or sachet of ispaghula husk (Metamucil® or Fibogel®) twice a day, can firm loose stools.

-

Topical creams and ointments

There are many over-the-counter creams or ointments that can be applied to the anus to reduce itch. Ointments contain petroleum jelly (Vasoline®) as the barrier compound, whereas creams are non-oily water based and may contain zinc oxide. These both act as a skin protectants and should be applied as a thin film to avoid excessive moisture. Zinc oxide on its own (Calmoseptine®) comes as both a cream and ointment. There are also numerous nappy rash creams. Bepanthen® contains vasoline, almond oil and dexpanthenol (Provitamin B5)

In addition, these products usually contain a small amount of one or more active ingredients. The active ingredients include an antiseptic (chlorhexidine), a local anaesthetic agent (lignocaine, benzocaine, cinchocaine) that numbs the area, corticosteroids (hydrocortisone, fluocortisone, prednisolone) that reduce inflammation, and vasoconstrictors (adrenaline) that make the blood vessels in the area become smaller, which may reduce swelling and help dry the area.

Products that contain a corticosteroid with a local anaesthetic include Proctosedyl®, Rectinol HC®, Scheriproct®, Ultraproct®. Others contain a vasoconstrictor with local anaesthetic (Rectinol®).

-

Antihistamines

Antihistamines have been shown to reduce itch[2]. However, most are sedative, and are best taken in the evening. These can be particularly useful for nocturnal itch.

-

Corticosteroid ointments & creams

Stronger 1% corticosteroid ointments or creams containing hydrocortisone (Egorcort® Sigmacort®) betamethasone (Diprosone®) may be obtained with a prescription, and have been shown to reduce inflammation and relieve itching [3-4]. They should not be used long term (i.e. more than a few days to two weeks), as chronic use can cause permanent damage to the skin.

-

Topical capsaicin

Topical capsaicin cream (Zostrix®) is a novel agent that has achieved success rates of up to 70%. It causes a low grade burning sensation, that over time, produces inhibitory neural feedback at the spinal cord level which decreases the perception of itch[5]. It comes in a 45g with 0.025% the standard strength sold as Zostrix®, 0.075% strength (Zostrix HP®) and is quite affordable costing approximately $20.00-$25.00.

-

Methylene Blue Tattooing

There is good evidence for high success rates with methylene blue tattooing for even severe intractable cases of idiopathic pruritus ani that have not responded to the above conservative measures[6]. An initial Australian study described high satisfaction rates in over 96%, with complete resolution after a single treatment in 57%[7]. Salvage treatment with an additional tattooing at 1 month in non responders is recommended [8]. A more recent South Korean long term follow up study of 63 patients at 3 years using a more dilute form of methylene blue (5 ml of 1% methylene blue mixed with 15 ml of 1% lidocaine) showed success rates of 92.5% following methylene blue tattooing. [9]. Steroid can also be added to the mix [10]. The mechanism of action is thought to be due to destruction of nerve endings in the peri-anal skin. The potential risks of methylene blue include skin necrosis and the very rare case of anaphylaxis has been reported [11]. Therefore tattooing with methylene blue should occur in a hospital facility with full resuscitative support available.

WHAT TO EXPECT BEFORE AND AFTER HAVING ANAL TATTOOING?

-

Fasting and Bowel Preparation

Unless you are also having a colonoscopy, a normal diet without bowel preparation, is required the day before surgery. You need to fast from midnight the night before if your surgery is scheduled for the morning, or from 7am if scheduled for the afternoon. You will be admitted as a day-stay procedure.

-

Recovery and transport

Following your procedure, you will recover for a hour until the effects of sedatives have worn off. You should not drive yourself home after your procedure and should have someone organised (a friend or relative) to accompany you.

-

Bleeding

Spotting of blood will occur from the injection sites. Blue discoloration of urine and to the perianal region will persist for some time. A sanitary napkin will be needed to prevent staining of your underwear.

-

Pain

For pain, a non-steroidal is recommended such as 400mg of ibuprofen (Brufen®) along with 2 tablets of paracetamol (Panadol®). This should only be taken if needed, and can be taken up to three times a day for five days. Stronger pain killers such as tapentadol (Palexia IR®) may be required in the first 24 hours. Strong opioid medications such as oxycodone (Endone®) are rarely needed, and should be avoided or used sparingly as they highly addictive and cause constipation. Where a chronic neuropathic component to the itch is present, atypical agents such as amitryptyline (Endep®) or pregabalin (Lyrica®) may be indicated.

-

Follow-up

You should follow up with your colorectal surgeon in 3-4 weeks following your surgery to review your condition and discuss further management if indicated. Occasionally non-responders require a second tattooing at one month to achieve relief [8].

REFERENCES

- Park JG. Coloproctology. 2. Seoul: Ilchokak; 2000. pp. 215–219.

- Siddiqi S. Vijay V. Ward M. Mahendran R. Warren S. Pruritus ani. Ann R Coll Surg Eng. 90(6):457-63, 2008.

- Markell KW. Billingham RP. Pruritus ani: etiology and management. Surg Clin N Am. 90(1):125-35, 2010.

- Al-Ghnaniem R. Short K. Pullen A. Fuller LC. Rennie JA. Leather AJ. 1% hydrocortisone ointment is an effective treatment of pruritus ani: a pilot randomized controlled crossover trial. Int J Col Dis. 22(12):1463-7, 2007.

- Lysy J. Sistiery-Ittah M. Israelit Y. Shmueli A. Strauss-Liviatan N. Mindrul V. Keret D. Goldin E. Topical capsaicin–a novel and effective treatment for idiopathic intractable pruritus ani: a randomised, placebo controlled, crossover study. Gut. 52(9):1323-6, 2003.

- Farouk R. Lee PW. Intradermal methylene blue injection for the treatment of intractable idiopathic pruritus ani. Br J Surg. 1997 May.

- Sutherland AD. Faragher IG. Frizelle FA. Intradermal injection of methylene blue for the treatment of refractory pruritus ani. Col Dis. 11(3):282-7, 2009.

- Mentes BB. Akin,Leventoglu S, et al. Intradermal methylene blue injection for the treatment of intractable idiopathic pruritus ani: results of 30 cases Coloproctol. 2004 Mar.

- Kim JH. Kim DH. & Lee YP. Long-term follow-up of intradermal injection of methylene blue for intractable, idiopathic pruritus ani. Tech Coloproctol. 2019 Feb.

- Markell KW, Billingham RP. Pruritis Ani: Etiology and Management. Surg Clin N Am 2010; 90: 125-137.

- Wahida FN. Sandovala JA. Severe anaphylactic shock due to methylene blue dye J. Ped Surg, Vol 2, Issue 3, Mar 2014, p 117-118.

ANAL WARTS

Anal warts (also called Condyloma Acuminata) result from previous infection with the Human Papilloma Virus (HPV).

CAUSE

Over 90% of anal warts are due to infection with HPV subtypes 6 & 11. These are rarely associated with anal cancer. Less than 10% of anal warts are due to infection with HPV Serotypes 16 & 18. However, serotypes 16 & 18 are both strongly associated with risk of developing anal cancer. Immunosuppressed patients (e.g. HIV) are at higher risk of infection. The highest risk population are the HIV male population, particularly those men who have sex with men (HIV – MSM).

SYMPTOMS

Perianal warts frequently itch, bleed and result in perianal wetness. There may be an associated lump. They are often confused for a haemorrhoid.

INVESTIGATION

-

Biopsy and Histopathology

Peri-anal warts are usually clinically apparent. They range from small pinkish-white small lesions to much larger lesions that are cauliflower in appearance. Their diagnosis is confirmed on histology from biopsy.

-

Viral Testing

Viral tests for HPV virus are available which are able to differentiate the serotype of HPV responsible. However, currently, there is no consensus opinion or convincing evidence of a benefit of routine testing for viral HPV serotypes. This is because viral serotypes are often cleared over time, and with ongoing sexual activity and new exposures, infection with different serotypes or a variety of serotypes may occur.

-

PAP smear

Although the PAP smear is currently used in Australia for cervical cancer screening, its role for anal cancer is less clear. PAP smear testing mainly has a role as a research tool in screening for Anal Intraepithelial Neoplasia (AIN). The poor sensitivity of the PAP smear remains an issue.

-

High Resolution Anoscopy

High resolution anoscopy with acetic acid staining is for excluding Anal Intra-epithelial Neoplasia (AIN) in high risk individuals such as HIV positive men who have sex with men (HIV-MSM). There are currently only five high resolution anoscopes in Australia, limiting their use, and currently there are no Australian guidelines on how often this should be performed.

COURSE

Most non-immunocompromised patients clear their warts over time, although repeated treatments may be needed to obtain full clearance. There is a long-term risk of Anal Intra-epithelial Neoplasia (AIN) with warts, particularly those due to HPV serotypes 16 & 18. High Grade Anal Intraepithelial Neoplasia (AIN) has a 10% chance progressing to Anal Cancer over a 5-year period.

PREVENTION

Anal warts are sexually transmitted, and spread by direct skin contact and are avoided by having protected intercourse. Barrier methods (condoms) help prevent against, but do not eliminate the risk of wart virus transmission.

VACCINATION

The HPV vaccine (Gardasil®) prevents infection against HPV serotypes 6, 11, 16 & 18 known to cause warts. But more importantly the HPV vaccine protects against serotypes 16 & 18 which are known to cause anal cancer. To be most effective, vaccination should be given early in life, preferably prior to sexual activity before exposure to the wart virus. There is still some benefit of vaccination to those who already have anal warts or high grade dysplasia, as the vaccine may allow clearance of the virus, and also protect against other serotypes they may not have come into contact with.

Since February 2013, free HPV vaccine (Gardasil®) has been provided through the school-based program for all males and females aged 12-13 years occurring in the first year of secondary school. The Gardisil® vaccine costs $153.43 each, and is recommended repeating at 3 and 6 months.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

Medical therapy with topical agents such as podophyllin resins (Wartkill®), with or without acetic acid, tend to fail, and there are concerns about systemic toxicity when applied to large areas. It is therefore only suitable for small lesions, and should be applied once a week, with numerous treatments usually required.

Podophyllotoxin is more effective being the purified anti-wart compound, and is available in 0.5% solution (Condyline® paint). This can be administered twice a day for 3 days, followed by 4 days of no treatment, and this cycle is repeated for four cycles. It is successful in less than 70% of cases and causes ulceration in 10-20% of cases.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgical management mainly consists of electro-cautery (diathermy) to de-bulk or reduce the size of the lesions, or excision, where the entire lesions is removed, including a full thickness excision of involved skin. Whilst diathermy to debulk the size of warts is less painful than excision, it is also unlikely to be curative. Excision of the entire wart with full-thickness excision of skin, is quite painful, and 5 days of analgesics, rest, and salt water baths is required. It is not uncommon for small warts to return, and these require excision as soon as they are noticed, to allow complete eradication of the wart virus.

WHAT TO EXPECT PRE AND POST OPERATIVELY FOR ANAL WART SURGERY

-

Fasting and Bowel Preparation

Unless you are also having a colonoscopy, a normal diet without bowel preparation, is required the day before surgery. You need to fast from midnight the night before if your surgery is scheduled for the morning, or from 7am if scheduled for the afternoon. You will be admitted as a day-stay procedure. You will receive a fleet® enema 1 hour prior to your operation.

-

Recovery and transport

Following your procedure, you will recover for an hour until the effects of sedatives have worn off. You should not drive yourself home after your procedure and should have someone organised (a friend or relative) to accompany you.

-

Bleeding

Spotting of blood will occur for 5 days following you procedure, and a sanitary napkin will be needed to prevent staining of your underwear. Bleeding will typically occur after opening your bowels. If the bleeding is more than a couple of teaspoons a day, notify your surgeon.

-

Laxatives

You should remain on regular laxatives and simple analgesics for 1 week. A tablespoon of natural Isphagula husk (Metamucil® or Fibogel®) twice daily is usually enough. If constipation develops, 30ml of lactulose (Duphalac®) twice daily is recommended.

-

Pain control

The amount of pain will depend on the amount of surgery performed to the perianal region. If only small excisions are performed, there may be very little pain, but for large ulcers to the anal region pain may be an issue. For pain, a non-steroidal is recommended such as 400mg of ibuprofen (Brufen®) along with 2 tablets of paracetamol. This should be taken regularly three times a day for five days. Opioid medications (Endone®) may sometimes be needed, but should be used sparingly as they cause constipation.

-

Sitz Baths

Twice daily warm to hot salt water (Sitz) bathing to the anal region is soothing and antiseptic, and should be done for 1 week following your procedure. Put a handful of salt into a shallow bath of warm-to-hot water and sit there for 10-15 minutes.

-

Follow-up

You should follow up with your colorectal surgeon in 6-8 weeks following your surgery to review your wound and discuss further management if indicated.

HAEMORRHOIDS

INTERNAL HAEMORRHOIDS

Internal haemorrhoids are vascular structures inside the anal canal which help with stool control. Normally they act as cushions that provide a water and air-tight seal preventing incontinence. When they become enlarged, they can bleed, or cause pain, or occasionally fall outside the anus (prolapse), sometimes to the point where they will not go back in again (irreducible prolapse). This can lead to the anus going into spasm, which leads to further swelling and engorgement. This may lead to a progressive increase in size of the haemorrhoid, eventually cutting off its own blood supply resulting in strangulation.

Internal haemorrhoids, so long as they remain internal, are rarely painful, but are prone to bleeding, particularly with a bowel motion. Typically bleeding is only on the toilet paper after wiping, with blood on the stool, but not mixed in the stool. When internal haemorrhoids fall outside the anus (prolapse), they can become extremely painful, especially if strangulation occurs.

EXTERNAL HAEMORRHOIDS

An external haemorrhoid is a very small hard blue lump much like a blood blister that is completely external to the anus and arises from the external vascular channels. It often presents as a sudden painful lump. It usually settles without surgery, but occasionally when very large, requires surgery for symptom relief.

GRADES OF INTERNAL HAEMORRHOIDS

Internal haemorrhoids can be further graded according to whether they are in the anus or have fallen out (prolapsed).

- Grade I – Completely internal, do not fall out (no prolapse)

- Grade II – Fall out (prolapse) on straining but go back in by itself.

- Grade III – Fall out (prolapse) on straining and stay out, and only go back if pushed back.

- Grade IV – Fall out (prolapse), and will not push back in. May be very painful due to strangulation.

PROGRESSION OF INTERNAL HAEMORROIDS

Untreated internal haemorrhoids (Grade I) can eventually enlarge to the point where they fall out (prolapse) and won’t go back in (Grade IV).

INVESTIGATIONS

Your colorectal surgeon will need to examine you to make the diagnosis. Rectal bleeding requires proper attention and examination, and frequently a colonoscopy is indicated to exclude other conditions that can cause bleeding that are frequently mistaken for haemorrhoids. Anal fissures are commonly mistaken for haemorrhoids, as they cause pain and bleeding while having a bowel motion.

PREVENTION OF HAEMORRHOIDS

Prevention is the best way to avoid haemorrhoids. This involves keeping the stools soft so they pass easily, decreasing pressure and straining. The urge to have a bowel motion should not be suppressed. Rather, one should be encouraged to empty bowels as soon as possible after the urge occurs. Regular exercise and increased fibre in the diet help reduce constipation and straining by producing stools that are softer and easier to pass. The least possible time should be spent on the toilet, and this may require removing the newspaper or magazines from the toilet to avoiding reading while on the toilet.

MEDICAL TREATMENT

Initial treatment consists of increasing fibre intake, oral fluids to maintain hydration, non-steroidal (NSAID) and simple non-opioid analgesics, warm to hot salt water (Sitz) baths, and rest. Surgery is reserved for those who fail to improve following these measures.

TOPICAL AGENTS

There are many topical agents and suppositories available for the treatment of haemorrhoids. Their main aim is to prevent thrombosis or itch. There is little evidence to support their use. Common ointments include those containing a combination of a zinc oxide barrier with a local anaesthetic (e.g. Rectinol® or Anusol Plus®) or a combination of corticosteroid with local anaesthetic (e.g. Scheriproct® and Proctosedyl®). Although these do not treat the underlying cause of haemorrhoids, they may partly reduce the pain and inflammation responsible for the itch. Thrombosed prolapsed haemorrhoids may cause anal spasm which is occasionally relieved with topical nitrate ointments such as Rectogesic®.

ENDOSCOPIC PROCEDURES

-

Rubber Band Ligation (RBL)

Rubber band ligation (RBL) is a procedure where elastic bands are applied to the internal haemorrhoid at least 1 cm above the dentate line. These eventually slough off within a week. This is a painless procedure unless the band is placed too close to the dentate line. If this occurs, intense pain may result.

This convenient and relatively non-invasive procedure is successful in the short-term in over 70% of cases. Recurrence remains as high as 30%.

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

-

Doppler-guided haemorrhoid artery ligation (HAL)

Doppler-guided haemorrhoid artery ligation (HAL) involves the use of a doppler to identify the arterial vascular pedicle, which is then tied off with a stitch. This reduces blood flow to the haemorrhoid, which over time shrinks the size of the haemorrhoid. It is suited for internal haemorrhoids and has the benefit of being minimally invasive.

This convenient and relatively non-invasive procedure is successful in the short-term in over 70% of cases. Recurrence remains as high as 30%.

-

Recto Anal Repair

A doppler-guided recto anal repair (RAR) involves that placement of a running suture along the length of the prolapsing haemorrhoid, which is then tied snug, thereby pulling the haemorrhoid back up into the upper anal canal. It usually follows haemorrhoid artery ligation (HAL).

-

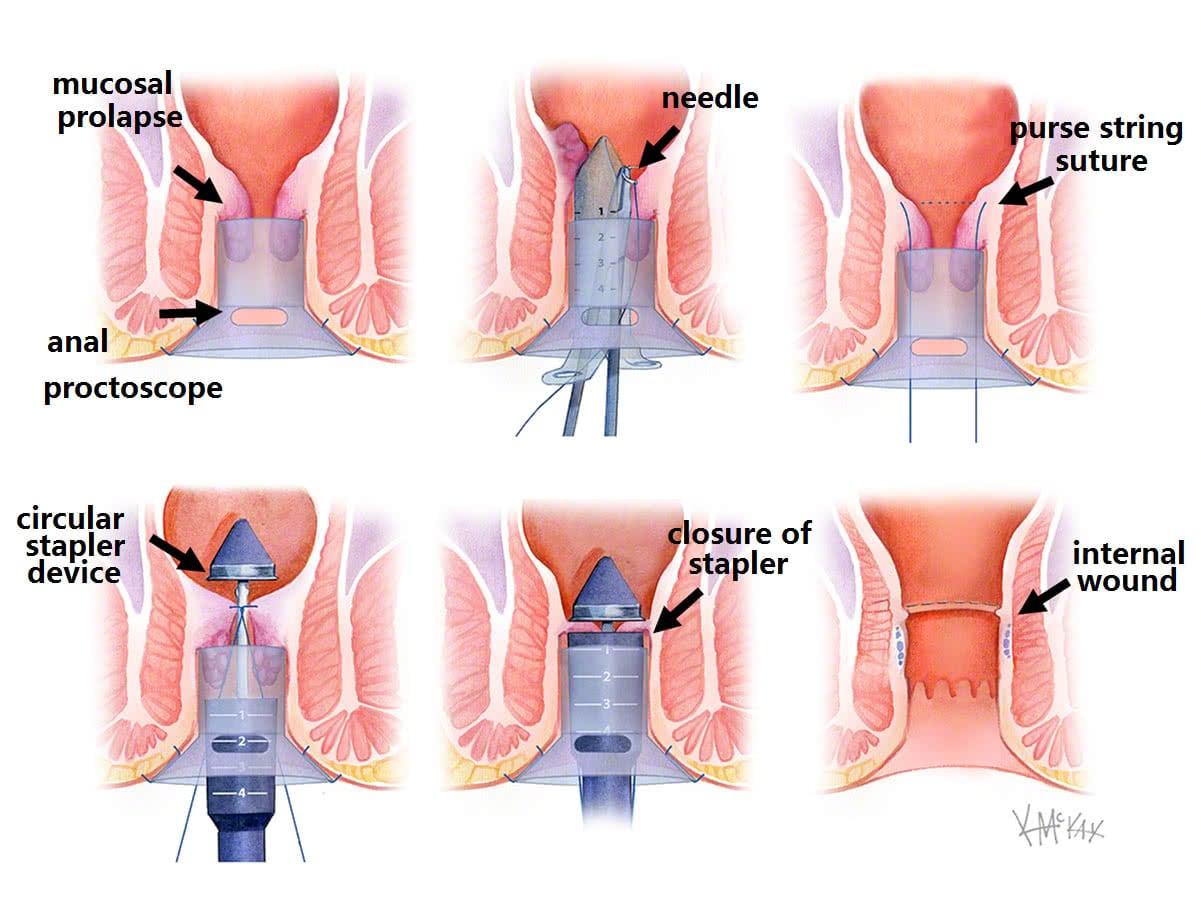

Stapled haemorrhoidectomy

Stapled haemorrhoidectomy uses a circular stapling device that removes a ring of haemorrhoid tissue and mucosa (much like a doughnut) within the upper anal canal. This has the benefit of avoiding an open wound and having less pain than an open haemorrhoidectomy (when stapler positioning is high in the anal canal). It is only suitable for internal haemorrhoids of moderate size. It is not suitable for very large haemorrhoids, or those with significant prolapse or external component.

-

Traditional haemorrhoidectomy

Haemorrhoidectomy is the surgical removal of haemorrhoid tissue. As you look at the anus, most haemorrhoids are located in the 3, 7 and 11 O’clock position. Excision of these three haemorrhoid cushions leaves three raw sores that are said to give the appearance of a “clover” (Fig 2). Amazingly these sores, with the aid of warm to hot salt water (Sitz) baths, always heal, but can be painful in the first few days following surgery.

WHAT TO EXPECT PRE AND POST OPERATIVELY FOR HAEMORRHOID SURGERY

-

Fasting and Bowel Preparation

Following your procedure, you will recover for an hour until the effects of sedatives have worn off. You should not drive yourself home after your procedure and should have someone organised (a friend or relative) to accompany you.

-

Recovery and transport

Following your procedure, you will recover for an hour until the effects of sedatives have worn off. You should not drive yourself home after your procedure and should have someone organised (a friend or relative) to accompany you.

-

Bleeding

Spotting of blood will occur for 5 days following your procedure, and a sanitary napkin will be needed to prevent staining of your underwear. Bleeding will typically occur after opening your bowels. If the bleeding is more than a couple of teaspoons a day, notify your surgeon. Bleeding following rubber band ligation typically occurs 7-9 days following banding, and may require a course of 400mg of metranidazole (Flagyl®) three times a day for 5 days to settle it down.

-

Laxatives

You should remain on natural laxatives for the first week. One tablespoon of natural isphagula husk (Metamucil® or Fibogel®) twice daily is recommended. If you are taking constipating opioid medication such as oxycodone (Endone), then regular Movicol ® once or twice daily is recommended.

-

Pain control

For pain, a nonsteroidal is recommended such as 400mg of ibuprofen (Brufen®) along with 2 tablets of paracetamol. This should be taken regularly three times a day for five days. Opioid medications such as oxycodone (Endone®) may sometimes be needed, but should be used sparingly as they cause constipation. Combined oxycondone and naloxone (Targin®) may be a better option, with less risk of constipation.

-

Topical Creams

Glycerine trinitate (Rectogesic®) ointment applied topically to the anus three times a day can be useful in preventing anal sphincter spasm and the development of an anal fissure at the wound site.

-

Sitz Baths

Twice daily warm to hot salt water (Sitz) bathing to the anal region is soothing and antiseptic, and should be done for 1 week following your procedure. Put a handful of salt into a shallow bath of warm-to-hot water and sit there for 10-20 minutes. Alternatively, if a bath is not available squat in the shower and soak with shower faucet.

-

Cleanliness

Avoid scratchy toilet paper after bowel movements. Flushable (dissolvable) Kleenex wipes, or bidet (water) are preferable in the first 1-2 weeks following your surgery.

-

Follow-up

You should call 1300 265 666 to make a follow up appointment with your colorectal surgeon in 2-6 weeks following your surgery to review your wound and discuss further management if indicated.