RECTAL CONDITIONS

Colorectal Surgeons Sydney are experienced with a variety of Rectal Conditions, including:

PROCTITIS

Proctitis is inflammation of the lining (mucosa) of the rectum.

Cause

There are many causes of proctitis, however in some cases the exact cause is still not known. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is responsible for the vast majority of cases of proctitis, however the exact cause of IBD remains elusive. Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease are two common forms of IBD responsible for proctitis. A third form of IBD is “indeterminate colitis” where the criteria to diagnose as either ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease are not met. Ulcerative colitis always causes proctitis, whereas Crohn’s disease can involve any part of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) and doesn’t always cause proctitis. Others less common causes of proctitis, include those due to an injurious agent such as infection, radiation, and trauma.

Radiation proctitis

Radiation proctitis is most commonly a complication of radiotherapy received for prostate cancer (in men) and cervical cancer (in women). With increased use of radiotherapy, its incidence is on the rise.

Infective proctitis

Infective causes of proctitis include those same infections that cause infectious gastro and include viruses such as rotavirus, and bacteria such as clostridium difficile, shigella, campylobactor, and amoebae such as yersinea and entamoeba histolytica. Other infectious causes of proctitis include those due to sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), such as gonorrhoea, chlamydia, and herpes simplex virus 1 and 2.

Effects of proctitis

Proctitis causes a red and “angry” rectum, much like a rash or a sunburn of the lining (mucosa) of the rectum that is friable and easily bleeds and ulcerates. In Ulcerative colitis the rectum is always involved resulting in proctitis, and any colonic involvement is continuous with the rectum, whereas in proctitis due to Crohn’s disease, there may be patches of uninvolved mucosa between involved mucosa, (so called “skip lesions”). In ulcerative colitis, the proctitis is not as deep, involving only the superficial mucosa and submucosa. In Crohn’s disease the whole thickness of the rectal wall is involved. Crohn’s proctitis therefore is more likely to result in deep ulcers, that often are linear (serpigenous).

Proctitis due to irradiation has many similar features to that due to IBD. A history of previous exposure to radiotherapy and the onset of proctitis following this, along with the absence of typical IBD features on biopsy all favour a diagnosis of radiation proctitis.

Presentation

Bloody mucous discharge is the commonest symptom of proctitis. There may also be some associated diarrhoea, that is often blood-stained (dysentery). Fatigue and light-headedness, due to chronic blood loss and anaemia, can also result.

Diagnosis of proctitis

Stool cultures should be sent to test for common infective agents that may be responsible. Colonoscopy is necessary not only to make the diagnosis of proctitis, but also to exclude other conditions that can cause rectal bleeding. Colonoscopy also allows for real time images to be taken of the lining of the rectum which has a characteristic appearance with granular friability, bloody mucous discharge, and contact bleeding when the colonoscope touches the mucosa. Colonoscopy also allows for biopsies to be taken to allow definitive examination under a microscope, and to send the tissues for culture to exclude infective causes.

Is there a risk of cancer with proctitis?

Longstanding proctitis, particularly those caused by inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are associated with an increased risk of cancer transformation. The progression from proctitis to cancer is over a period of time. Early precancerous changes (dysplasia) begins as mild before becoming moderate, and in some cases becomes severe dysplasia, before finally becoming invasive cancer. Colonoscopy allows for visual inspection of the colon and rectum, as well as allowing for biopsies to be taken, to make sure that high grade dysplasia or cancer are not present.

Management of proctitis

Infective proctitis need to be identified, and the infective agent treated with antibiotics, although these represent the minority. Most other non-infectious cases of proctitis settle with suppositories or rectal foam containing prednisone (Predsol®). In cases due to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) enemas containing salazopyrine(Salofalk®) may be used.

Irradiation proctitis frequently resolves in the months following radiation treatment. Cases which persist can be difficult to treat. Troublesome bleeding can improve with topical application of formalin, or with APC (argon-plasma coagulation) or laser.

Role of surgery for proctitis

Occasionally surgery is indicated for severe cases of proctitis due to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). In other cases surgery is indicated to reduce the risk of cancer where high grade dysplasia is found on routine biopsies.

In ulcerative colitis the rectum can be removed completely and a new rectum constructed using small bowel (called a “J pouch”) which is then joined directly to the anus. There is some evidence that this can also be done for “indeterminate proctitis”, however formation of a “J-pouch” is associated with a high failure rate when used for proctitis due to Crohn’s disease, and is generally discouraged.

RECTAL BLEEDING

‘Rectal’ bleeding (hematochezia) refers to the passage of red blood from the anus, often mixed with stools and/or blood clots.

It is called ‘rectal’ bleeding because the rectum lies immediately above the anus, and although the bleeding may be coming from the rectum, it may also be coming from higher up in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT).

Causes of rectal bleeding

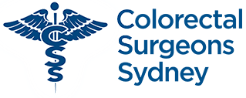

Rectal bleeding is commonly due to diverticular disease. It can also be due to colitis, polyps, or haemorrhoids.

Severity of rectal bleeding

-

Mild bleeding

The severity of rectal bleeding varies widely. Usually rectal bleeding is mild and stops on its own. Frequently only a few drops of fresh blood are passed on straining or on wiping. This can appear dramatic, as it turns the water in the toilet cistern pink-red. Alternatively, one may see spots of blood on the tissue paper. Others may report brief passage of a spoonful or two of blood.

Mild rectal bleeding usually settles on its own, but warrants referral to a colorectal surgeon for further investigation.

-

Moderate to severe bleeding

Rectal bleeding also may be moderate or severe. Patients with moderate bleeding will repeatedly pass larger amounts of bright or dark red (maroon-coloured) blood often mixed with stools and/or blood clots. Patients with severe bleeding may pass several bowel movements or a single bowel movement containing a large amount of blood. Moderate or severe rectal bleeding can quickly lead to significant blood loss resulting in symptoms of weakness, dizziness, light-headedness and a drop in blood pressure when going from the sitting or lying position to the standing position. Occasionally the bleeding may be so severe as to cause shock from the loss of blood.

Moderate or severe rectal bleeding usually requires admission to hospital for further investigation and management. Occasionally a blood transfusion is required. A CT angiogram with intravenous contrast may show the site of bleeding, and allow for this bleeding vessel to be blocked using angiography.

Site of rectal bleeding

Most rectal bleeding comes from the lower gastrointestinal tract (i.e. the anus, rectum or colon). Less commonly brisk bleeding from the upper gastrointestinal tract (oesophagus, stomach and small intestine) is responsible.

Bright red versus maroon versus black

The colour of blood during rectal bleeding often depends on the location of the bleeding in the gastrointestinal tract. Generally, the closer the bleeding site is to the anus, the brighter red the blood will be. Therefore bleeding from the anus, rectum, and the lower colon tends to be bright red, whereas bleeding from higher up in the colon tends to be dark red or maroon-coloured. Bleeding from the upper gastrointestinal tract (i.e. oesophagus, stomach and small intestine) can be black, “tarry” (sticky) and foul smelling. The black, smelly and tarry stool is called melena. Melena occurs when the blood is exposed to acid and intestinal bacteria to break it down into chemicals (hematin) that are black. Therefore, melena usually signifies that the bleeding is from the upper gastrointestinal tract (for example, bleeding from ulcers in the stomach or the duodenum or from the small intestine).

Occasionally, brisk large bleeds from the upper gastrointestinal tract (GIT) (oesophagus, stomach and small intestine) occur so quickly, that acid and bacteria do not have time to change the colour of blood, and rectal bleeding can be bright red in colour in this instance. This warrants emergency admission to hospital as shock can result if left untreated.

Occult bleeding

Rectal bleeding that is visible needs to be distinguished from another type of gastrointestinal (GIT) bleeding, which is not visible referred to as occult bleeding. Occult bleeding refers to the slow loss of blood usually from high up in the colon, or even from the upper GIT (oesophagus, stomach or small intestine), that leads to anaemia. The blood is detected only by testing the stool for blood using faecal occult blood testing (FOBT).

Colonoscopy and gastroscopy

Referral to a colorectal surgeon to discuss performing a colonoscopy and gastroscopy is important in determining the cause of rectal bleeding. This will allow complete visualisation of the lower GIT (anus, rectum and colon) as well as some of the upper GIT (oesophagus, stomach and duodenum). It will also allow for biopsies to be taken.

RECTAL PROLAPSE

Rectal prolapse describes a condition where either the lining or entire wall of the rectum becomes loose and falls into, or even out of, the rectum through the anus.

Types of rectal prolapse

There are two types of rectal prolapse:

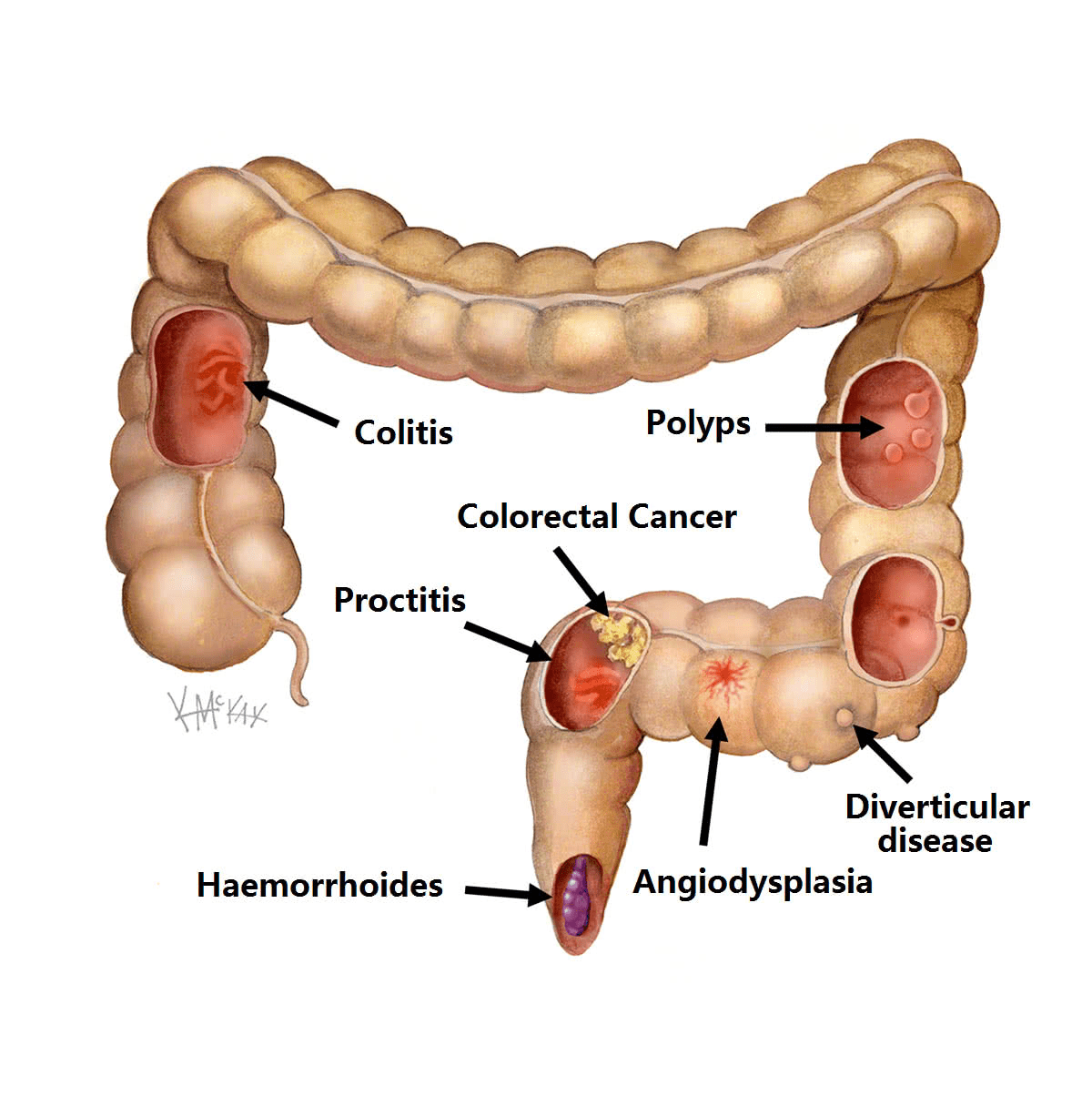

- Partial thickness prolapse (also called internal intussusception).

- Full-thickness prolapse (also called external prolapse).

-

Partial-thickness rectal prolapse

Partial thickness rectal prolapse, is where the lining of the rectum (mucosa) becomes loose and falls downs into the lumen of the anal canal when straining. Because it is not full thickness, it rarely prolapses enough to protrude through the anus. Partial thickness prolapse may cause some degree of blockage in the rectum when straining (obstructive defecation), and may be a contributing factor to constipation. It can also lead to a feeling of incomplete evacuation.

-

Full-thickness rectal prolapse

Full thickness rectal prolapse is where the entire wall of the rectum becomes so loose that on straining it telescopes on itself to such an extent that it falls out being visible external to the anus. Full thickness rectal prolapse is often mistaken for a haemorrhoid, as bleeding and mucous discharge are common symptoms.

Cause

Rectal prolapse is caused by weakening of the muscular pelvic floor and ligaments that support the rectum keeping it in place. Rectal prolapse may be associated with advanced age, weight loss, long term constipation, long term straining during defecation, previous pregnancy or obstetric trauma and multiple childbirths. Frequently in women rectal prolapse is also associated with a rectocele. which is a weakness in the rectal wall where it balloons into the vagina.

Symptoms

The commonest symptom of rectal prolapse is mucous discharge from the anus or occasional bleeding. The prolapse may be noticed as bulging mucosa typically on straining. Rectal prolapse may give the sensation of constipation (obstructive defecation) or incomplete emptying when having a bowel motion.

Investigation

Full thickness prolapse is clearly evident with bearing down with eversion of the rectum and a protruding bulge. Therefore, this diagnosis is made clinically. Partial thickness (mucosal) prolapse can sometimes also be severe enough to result in prolapsing mucosa that bulges and is visible external to the anal sphincter on straining (Figure 1a). More typically however, it is less obvious, and is visible on defecating proctogram, a real time x-ray taken while defecating. Rectal prolapse may also be more obvious in the relaxed state, such as under general anaesthesia.

Colonoscopy

All patients with rectal prolapse and symptoms of constipation or incomplete evacuation, require a complete colonoscopy to rule out other pathology of the colon that can result in these symptoms.

Defecating proctography

Defecating proctography is useful for documenting partial thickness rectal prolapse causing obstructive defecation.

Transit studies

Those with constipation as the major feature without obvious full-thickness external prolapse, should have transit studies to exclude slow transit constipation prior to surgery.

Prevention

There is little that can be done to prevent rectal prolapse. Any procedure or condition that weakens the pelvic floor (e.g. childbirth or obstetric trauma), increases the risk of rectal prolapse later in life.

Course

Mild rectal prolapse, may progress and become more advanced with time. Partial thickness prolapse can in some cases progress to full thickness prolapse. Typically prolapse occurs during straining when having a bowel movement, or when sneezing or coughing. As it develops, it occurs more frequently, even throughout daily activities such as walking. Finally, it may be prolapsed continually, and in the worse form, ceases to retract being irreducible.

Medical management

The constipating effects of partial thickness rectal prolapse may be treated by a diet high in fibre and regular laxatives. This leads to less firm stools and the avoidance of straining. A sanitary pad is often required to deal with the mucous discharge and bleeding.

Surgical management

The alternative is surgery. Surgery is generally of two types:

- Perineal surgery.

- Abdominal surgery.

-

Perineal surgery

Perineal surgery is where the surgery is performed on the rectum approached from the anus. It does not involve major abdominal surgery, and is particularly suited in the elderly and those with multiple medical conditions that would make abdominal surgery unsafe. Perineal procedures include those that deal only with partial thickness prolapse (STARR procedure, or stapled mucopexy), and those that deal with full thickness rectal prolapse (Delorme’s and Altimeier’s procedure)

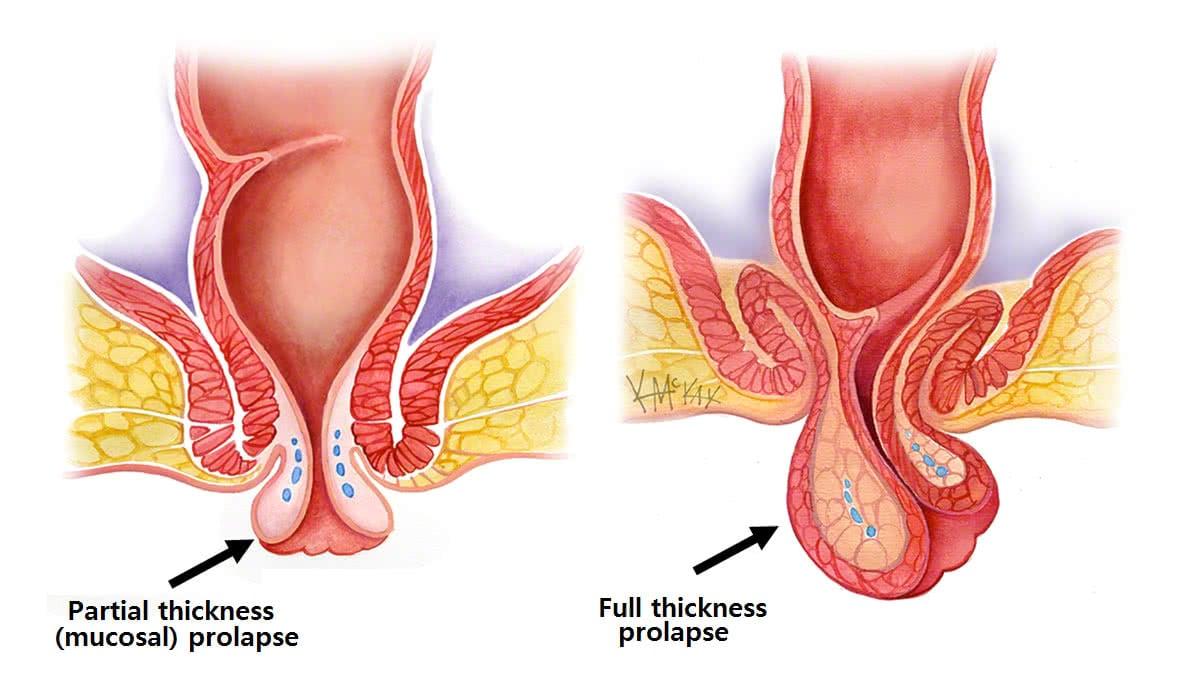

STARR Procedure (stapled mucopexy)

The STARR procedure is a stapled mucopexy suitable for partial thickness mucosal prolapse with an anterior rectocele. It is a repair where a circular staple removes a cuff of prolapsing mucosa. It has the benefit of being relatively painless, with no external incisions.

Delorme’s ProcedureThe Delorme’s procedure is where the redundant mucosa is excised, and re-joined after plication of the underlying muscle wall of the rectum. This plication helps serve as extra bulk to the anal sphincter, and is thought to improve incontinence. It main disadvantage is a high recurrence rate of up to 30%.

Altimeier’s Procedure

An Altimeier’s procedure, is also a perineal procedure, where there is full thickness excision of the portion of rectum that is prolapsed, and the two ends are sewn together. This is more suitable than Delorme’s, when the prolapse is excessive or non-reducible, or where the patient also has constipation. It has a lower recurrence rate than the Delorme’s procedure, but requires a bowel resection, and therefore carries a risk of 1-2% of a leak at the join (anastomosis).

These perineal procedures all have the benefit of being quick operations performed via the perineum (i.e. directly operating on the anus without the need for an abdominal approach). These may be a safe option, particularly for the older frail patient, but have a higher recurrence rate than abdominal procedures.

-

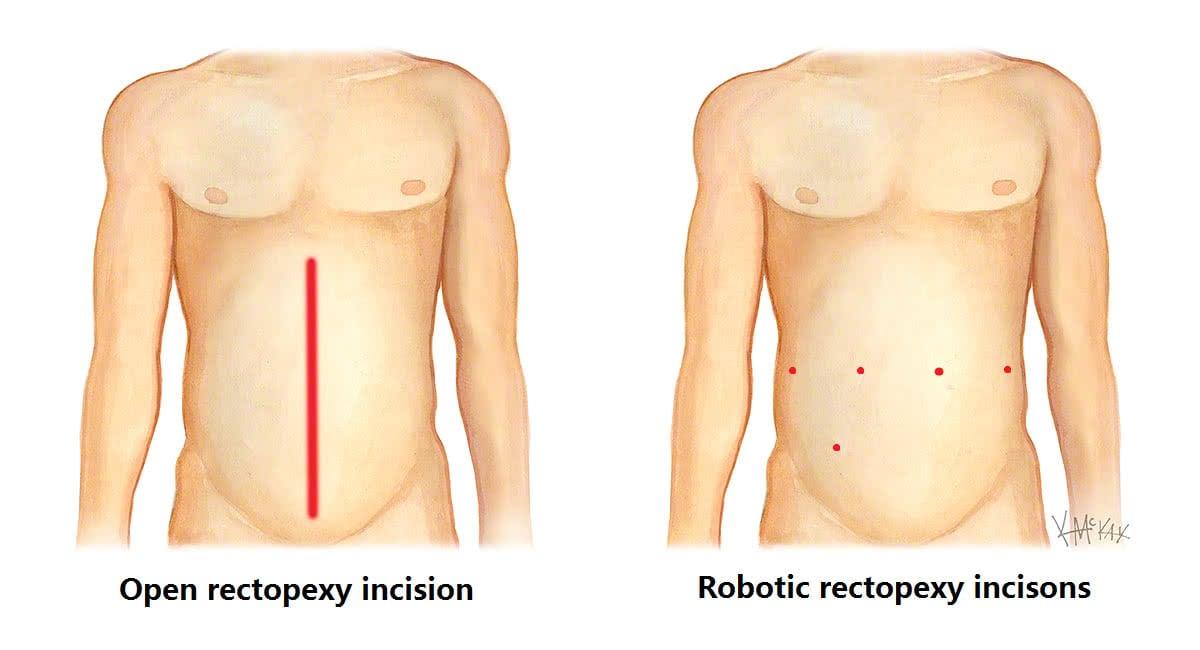

Abdominal surgery

Abdominal surgery involves mobilising the rectum, and suspending it, usually with mesh, to the bony prominence (sacral promontory) of the pelvis. Abdominal surgery for rectal prolapse is increasing being performed key hole (laparoscopic or robotically) with benefits of small incisions and less pain than traditional open surgery.

Patients with rectal prolapse without constipation as a major feature will benefit from a mesh rectopexy. Patients with rectal prolapse with constipation as a major feature may benefit from a slow transit study to rule out slow transit constipation. For those with constipation, resection rectopexy, where a portion of the redundant bowel is removed, may be preferable to mesh rectopexy, although the added risk of 1-2% of anastomotic leak is the major down-side of resection rectopexy.

Ventral Mesh Rectopexy

Ventral Mesh Rectopexy is a procedure involving the suspension and fixation of the front of the rectum and pelvic floor to the bony sacral promontory with a bio-dissolvable mesh. In this technique, the nerves to the rectum that enter from the back and side are preserved with mobilisation only from the front of the rectum. The preservation of these nerves is thought to improve rectal function and emptying, and reduce the risk of hind gut neuropathy and resultant constipation. Preservation of these nerves also prevents disorders of sexual function and fertility. There is no evidence that recurrence rates are higher with bio-dissolvable mesh compared with permanent mesh. The bio-dissolvable mesh also avoids the long-term complications of mesh infection and erosion reported with permanent mesh.

Robotic versus Laparoscopic Surgery

Robotic ventral mesh rectopexy with the da Vinci® platform is gaining increasing popularity and beginning to replace laparoscopic surgery due to the increased ease with which suturing is able to be performed using the robot within the narrow confines of the bony pelvis. This is already showing less blood loss and conversion to open rate when compared to the laparoscopic approach [1,2, 3]. This is largely due to the ability of the articulating miniature robotic arms to perform complex fine-motor movements within a confined space. The extra third arm also allows for excellent retraction within the narrow pelvis, and the three dimensional magnified view allows for visualization and preservation of the pre-sacral nerves preventing hind gut, sexual and fertility dysfunction.

The latest Xi da Vinci® robot, has narrow instruments and a camera less than 8mm in width, allowing all ports to be less than 8mm in size. This has the advantage of smaller cuts and less pain and early discharge and return to normal activities. The ability of the camera to fit through any of the 8mm ports (a features not present with earlier da Vinci® models) also allows for greater freedom and interchange of instruments when required, making multi-quadrant surgery much easier.

The 8mm incisions with the xi da Vinci® model are usually five in number as shown below, with one for the camera, three for robotic instruments, and one for the surgical assistant to assist with the passing of sutures, equipment as required.

What to expect prior to surgery for rectal prolapse

-

Clear Fluids

You will need to have only clear fluids the day before your surgery. Clear liquids are those that one can see through. When a clear liquid is in a container such as a bowl or glass, the container is visible through the substance. Examples of clear fluids include water, broth, apple juice, jelly, sports drinks such as Gatorade®, Lucozade® and Gastrolyte®. Try to drink at least 3-4 litres the day prior to your surgery.

-

Bowel Preparation

You will also require bowel prep to clean your colon. Take a Pico-sulfate (Picolax®) sachet (mixed in a glass of water) at 2pm, 4pm and 6pm the day before your procedure. If you are prone to constipation, the 4pm Picolax is replaced with a sachet of Glycoprep (mixed to a litre with water). You can purchase these from your chemist without needing a prescription.

-

Nil By Mouth

You need to be nil by mouth (i.e. no liquids) from midnight the night before if your surgery is scheduled for the morning, or from 6am if scheduled for the afternoon.

-

Admission Time

The exact time for your admission is finalised the day prior and you will receive a phone call in the morning at about 10am to inform you what time to present. This is normally 2 hours prior to the planned start time.

What to expect after surgery for rectal prolapse?

-

Diet

Immediately after your procedure you will be commenced on free fluids (semi thickened fluids such as custard, yoghurt, thin porridge). Once you have passed flatus, and any nausea has settled you will be commenced on a light diet.

-

Pain Relief

You will be given a Patient Controlled Analgesia (PCA) device to administer your own pain relief for the first 24 hours, then this will be replaced with oral pain killers, usually paracetamol, and a nonsteroidal such as Celcoxib® or Nurofen®, and if needed oral oxycodone (oxycontin®).

-

Laxatives

You will be on regular laxatives (Movicol®) from day 1, and should remain on this for 6 weeks. The dosage is individualised, with huge variation between patients. The usual starting dose is one Movicol® twice daily. This can be halved or doubled or quadrupled depending on the response. The aim is soft stool to avoid straining.

-

Exercise

Walking is encouraged from day one, as this improves your recovery and prevents against developing a venous clot and pneumonia. Gentle swimming or cross-trainer or cycling can occur after 48 hours. No vigorous running, jumping or exercises are recommended for 6 weeks after surgery.

-

Dressings

Water proof Comfeel® dressings will cover each of your 8mm incisions, and can be removed 7 days after surgery and simply left open.

-

Discharge Home

You will be discharged from hospital once you have opened your bowels and are tolerating a normal diet. This can range from 3 days to a week.

-

Regular medications

If not already done so, you are to go back on all your regular medications on discharge.

-

Follow-Up

Please ring 1300 265 666 to organise a follow-up appointment with your surgeon at 2-6 weeks after your procedure.

References

- Wong MT1, Meurette G, Rigaud J, Regenet N, Lehur PA. Robotic versus laparoscopic rectopexy for complex rectocele: a prospective comparison of short-term outcomes. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011 Mar;54(3):342-6.

- Mehmood RK1, Parker J, Bhuvimanian L, Qasem E, Mohammed AA, Zeeshan M, Grugel K, Carter P, Ahmed S. Short-term outcome of laparoscopic versus robotic ventral mesh rectopexy for full-thickness rectal prolapse. Is robotic superior? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014 Sep;29(9).

- Mantoo S1, Podevin J, Regenet N, Rigaud J, Lehur PA, Meurette G. Is robotic-assisted ventral mesh rectopexy superior to laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy in the management of obstructed defaecation? Colorectal Dis. 2013 Aug;15(8):e469-75.